In practice, this is often where customization decisions start to be misjudged. A corporate buyer approaches the factory with a purchase order for five thousand stainless steel tumblers. The specifications are detailed: laser-engraved company logo, custom powder coating, branded packaging. The commercial terms are negotiated, the unit price is agreed upon, and the delivery timeline is confirmed. From the buyer's perspective, this is a single order-a straightforward procurement transaction. But when the purchase order arrives at the factory floor, the project manager sees something entirely different. The order specifies five different powder coating colors, each in a quantity of one thousand units. Three different laser engraving designs are distributed across these color variations. Two different lid configurations are requested to accommodate different use cases within the organization. What the buyer perceives as "reasonable customization within a single order" translates, on the factory floor, into a production schedule that requires ten or more line changeovers, each consuming thirty to ninety minutes of non-productive setup time. The buyer has requested variety. The factory must deliver complexity. And the gap between these two understandings is where lead times extend, costs escalate, and delivery commitments begin to unravel.

This misjudgment is systematic, not occasional. Corporate buyers routinely structure drinkware orders to include multiple variations-different colors, different engraving designs, different component configurations-without recognizing that each variation introduces a discrete setup cost at the factory level. The assumption is that customization variety is additive: if one thousand tumblers in a single color configuration can be produced in ten days, then five thousand tumblers across five color configurations should take proportionally longer, perhaps twelve or fifteen days to account for the increased volume. But production time is not linear with respect to variety. It compounds. Each time the production line switches from one powder coating color to another, the coating equipment must be purged, cleaned, and recalibrated. Each time the laser engraving system transitions from one design file to another, the artwork must be loaded, the focal parameters must be adjusted, and test engravings must be verified. Each time the assembly line changes from one lid configuration to another, the feeding mechanisms must be reconfigured and the quality inspection protocols must be updated. These changeover activities do not scale with volume. They are fixed-time events that occur once per variation, regardless of whether that variation represents ten units or one thousand units.

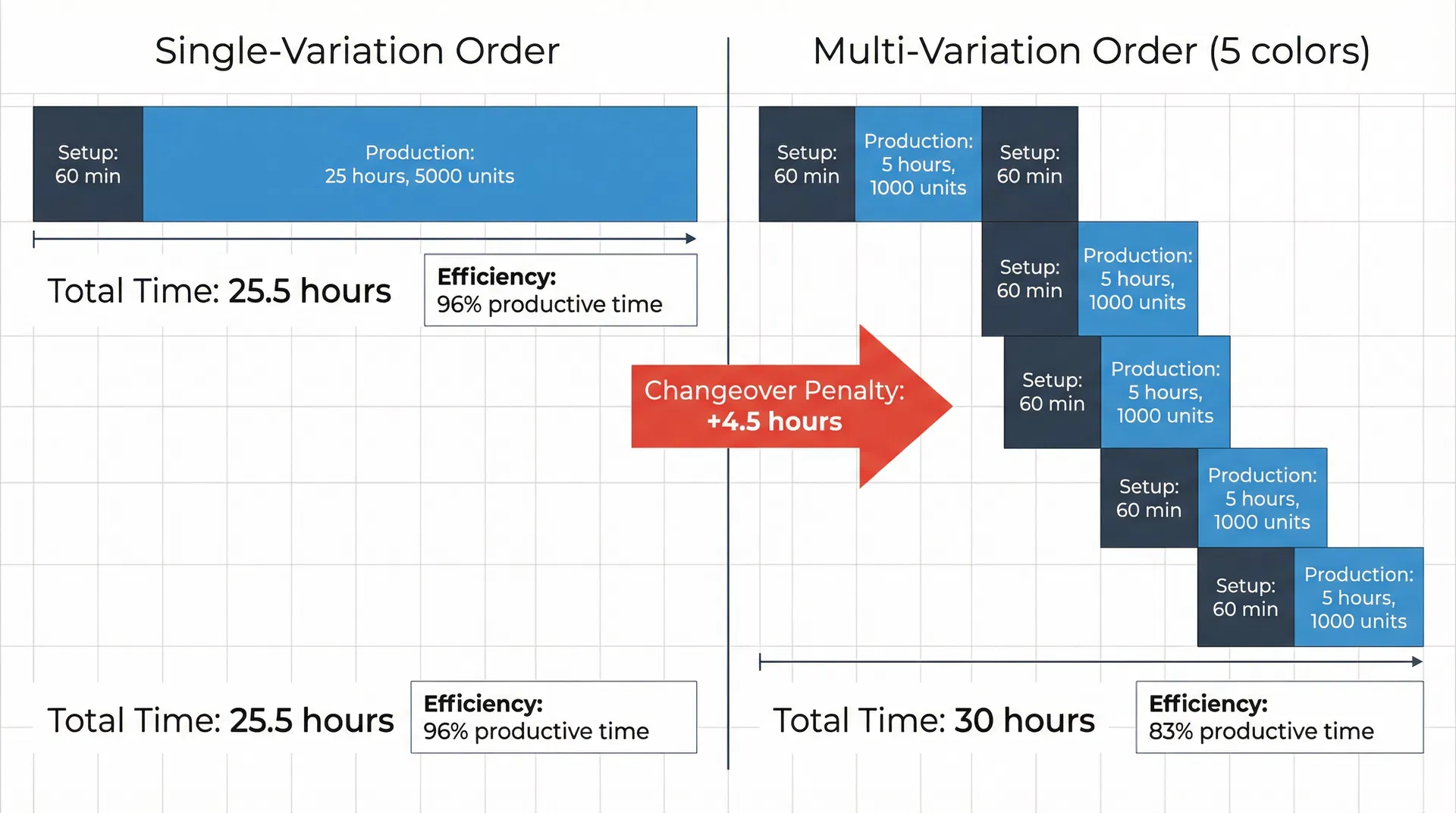

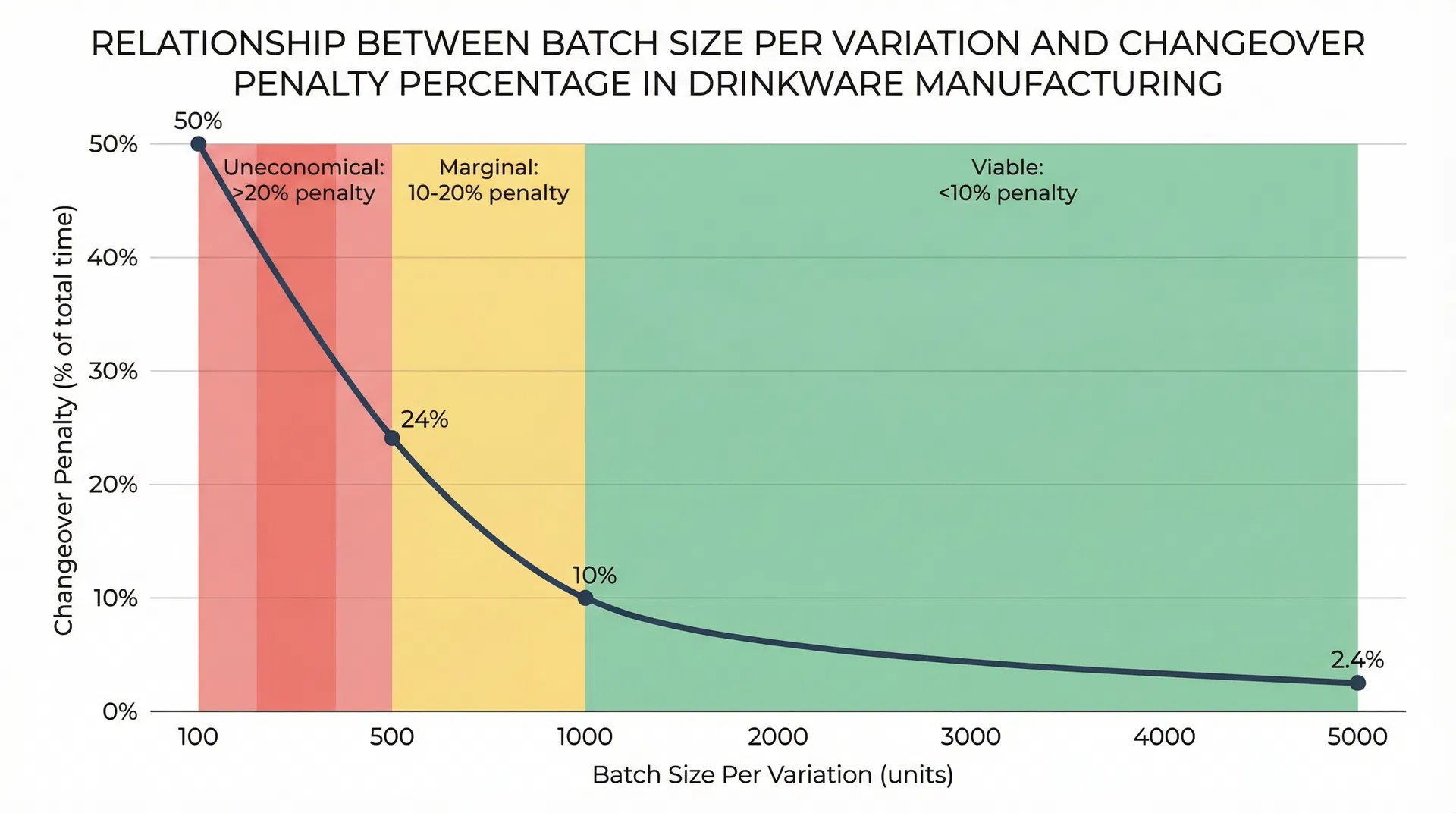

The economic structure of changeover time creates a threshold effect that buyers rarely anticipate. Consider a powder coating line that requires sixty minutes to complete a full changeover from one color to another. This sixty-minute window includes draining the previous color from the spray guns, flushing the system with solvent, loading the new powder color, adjusting the electrostatic charge settings, and running test pieces to verify color consistency and coating thickness. During this sixty-minute period, the line produces zero salable units. If the batch size for the new color is five thousand units, and the line's production rate is two hundred units per hour, the changeover time represents sixty minutes of downtime against twenty-five hours of productive run time-a changeover penalty of approximately two point four percent. This is manageable. The unit cost increase attributable to the changeover is negligible, and the delivery timeline absorbs the setup time without significant extension. But if the batch size for the new color is five hundred units, the same sixty-minute changeover now represents sixty minutes of downtime against two point five hours of productive run time-a changeover penalty of twenty-four percent. The unit cost impact is no longer negligible. The delivery timeline extends noticeably. And if the batch size drops to two hundred units, the changeover time equals the production run time, effectively doubling the total time required to produce that color variation.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. It is the operational reality that factories confront when buyers request high variety within a single purchase order. A five-thousand-unit order split evenly across ten color variations means ten changeovers, each consuming sixty minutes, for a total of six hundred minutes-ten hours-of non-productive setup time. If the buyer had instead committed to a single color variation for the entire five-thousand-unit order, those ten hours would have been productive manufacturing time, yielding an additional two thousand units. The factory has not become less efficient. The buyer has requested a production structure that inherently generates more downtime relative to output. And because this downtime cost is rarely made explicit during the quotation phase, the buyer proceeds under the assumption that variety is inexpensive, while the factory absorbs the changeover penalty as an unacknowledged cost burden that erodes margin and compresses the production schedule.

The compounding effect of variety becomes more severe when multiple customization layers are stacked within the same order. A buyer who requests five powder coating colors, three laser engraving designs, and two lid configurations is not requesting eight discrete variations. They are requesting a matrix of potential combinations, and the factory must determine which specific combinations are required and in what quantities. If the buyer specifies that each of the five colors should include all three engraving designs, that creates fifteen unique SKU configurations. If each of these fifteen configurations is further split between two lid types, the total number of unique SKUs rises to thirty. Even if the buyer clarifies that only certain combinations are needed-perhaps ten specific SKUs out of the thirty possible permutations-the factory still faces ten distinct production setups, each requiring its own changeover sequence. The laser engraving line must switch design files ten times. The assembly line must alternate between lid configurations multiple times. The packaging line must handle ten different label and insert variations. Each of these transitions consumes setup time, and the cumulative setup time can easily exceed the actual production time for small batch sizes per SKU.

The buyer's mental model of this transaction is fundamentally different from the factory's operational model. The buyer sees a single purchase order with a total quantity of five thousand units and a negotiated unit price. The factory sees ten or more discrete production runs, each with its own setup cost, each competing for line time, and each requiring coordination across multiple production stages. The buyer evaluates the order based on total cost and total delivery time. The factory evaluates the order based on cost per SKU, setup time per SKU, and the scheduling complexity of sequencing multiple small-batch runs through shared equipment. These two perspectives are not merely different-they are structurally incompatible. And because the customization conversation during the inquiry and quotation phase rarely surfaces this incompatibility, the misalignment persists until production begins, at which point the factory discovers that the committed delivery timeline cannot be met without either extending the schedule or prioritizing this order at the expense of other commitments.

The root cause of this misjudgment is that variety is treated as a specification attribute rather than as a production cost driver. When a buyer specifies "five colors" in the purchase order, they are describing a product characteristic. When the factory reads "five colors," they are calculating five changeover events, each with an associated time cost and each reducing the effective throughput of the coating line. The buyer's specification language does not encode the operational implications of that specification. A purchase order that lists "Quantity: 5000 units, Colors: Red (1000), Blue (1000), Green (1000), Black (1000), White (1000)" conveys the same information to the buyer as a purchase order that lists "Quantity: 5000 units, Color: Red (5000)." Both orders total five thousand units. Both orders specify powder coating. Both orders define the color palette. But from a production planning perspective, these two orders are radically different. The first order requires four more changeovers than the second order, extending the total production time by four to six hours and introducing four additional opportunities for color matching errors, coating defects, or scheduling conflicts.

The factory project manager's challenge is to translate the buyer's variety request into a production schedule that accurately reflects the changeover cost, and then to communicate that cost back to the buyer in a form that is commercially intelligible. This translation is not straightforward. The buyer does not think in terms of changeover minutes or setup ratios. They think in terms of unit price and delivery weeks. If the factory responds to a high-variety order by quoting a longer lead time or a higher unit price, the buyer may interpret this as the factory being less competitive or less capable, rather than as an accurate reflection of the production cost structure that the buyer's own variety request has created. The buyer may then seek alternative suppliers who quote shorter lead times or lower prices, not recognizing that those suppliers are either underestimating the changeover cost, absorbing it as a margin sacrifice, or planning to renegotiate the timeline once production realities become apparent.

The structurally sound approach is to front-load the variety cost discussion into the initial inquiry and quotation phase, before the purchase order is finalized. When a buyer requests a quote for custom tumblers and specifies multiple color variations, the factory's sales or technical team should provide a tiered quotation structure that makes the changeover cost explicit. For example: "Five thousand units in a single color: unit price eight dollars, lead time four weeks. Five thousand units split across five colors (one thousand units per color): unit price eight dollars fifty cents, lead time five weeks. Five thousand units split across ten colors (five hundred units per color): unit price nine dollars twenty cents, lead time six weeks." This pricing and timeline structure communicates that variety has a cost, and that the cost increases non-linearly as batch size per variation decreases. It allows the buyer to make an informed trade-off between variety and cost, rather than discovering the variety penalty only after the purchase order has been issued and the delivery timeline has been committed.

The alternative is to absorb the variety penalty as an invisible cost and hope that the buyer's future orders will be less complex, allowing the factory to recover margin on simpler, higher-volume runs. This is a gamble that often fails. Buyers who receive accommodating responses to high-variety initial orders tend to interpret that accommodation as evidence that variety is inexpensive, and they structure subsequent orders with even greater complexity. The factory becomes locked into a customer relationship where every order is a scheduling puzzle, every delivery timeline is at risk, and every margin calculation includes an unacknowledged changeover tax. Breaking this pattern requires making the variety cost visible and negotiable, rather than hidden and absorbed.

The interaction between order variety and factory scheduling introduces another layer of complexity that buyers rarely consider. A factory's production capacity is not a simple function of equipment speed and available hours. It is a function of how efficiently that equipment can be utilized given the mix of orders in the production queue. A coating line that can theoretically produce ten thousand units per week operates at that capacity only if it runs continuously on large batches with minimal changeovers. If the production queue is filled with small-batch, high-variety orders, each requiring frequent changeovers, the effective throughput of that line may drop to six or seven thousand units per week, even though the equipment itself has not changed. The buyer who submits a high-variety order is not merely consuming their proportional share of the factory's capacity-they are reducing the factory's overall capacity for all customers during the period when their order is being processed.

This capacity dilution effect is particularly acute when the buyer's order includes variations that are unique to that buyer and cannot be batched with other customers' orders. If five different buyers each order one thousand red tumblers in the same week, the factory can potentially batch all five thousand red units into a single production run, executing one changeover to serve five customers. But if one buyer orders one thousand units split across five unique custom colors that no other customer has requested, the factory must execute five changeovers to serve that single customer, and those changeovers cannot be amortized across other orders. The buyer who requests unique variety is, in effect, purchasing exclusive access to the production line during the changeover periods, even though they are not paying a premium that reflects that exclusivity.

The timing of when variety decisions are made also affects the changeover cost structure. If the buyer specifies all color variations and their respective quantities at the time of the initial purchase order, the factory can optimize the production sequence to minimize changeover frequency. For example, if the order includes both matte and glossy finishes in multiple colors, the factory can sequence all matte colors consecutively, then execute a single finish changeover, then run all glossy colors consecutively. This reduces the total number of changeovers compared to a sequence that alternates between matte and glossy finishes. But if the buyer issues the initial purchase order with only partial variety specifications-"five thousand units, colors to be confirmed later"-and then provides the color breakdown in stages as internal decisions are finalized, the factory loses the ability to optimize the production sequence. Each color confirmation may arrive at a different time, forcing the factory to slot that variation into whatever production window is available, regardless of whether it creates an efficient changeover sequence. The buyer perceives this staged specification process as flexible and responsive to their internal planning needs. The factory experiences it as a source of scheduling fragmentation and changeover cost escalation.

The certification and compliance dimension of variety adds yet another cost layer that is often invisible to the buyer. If the factory holds LFGB or FDA certification for a specific tumbler configuration-a particular steel grade, a particular powder coating formulation, a particular gasket material-that certification applies to that specific configuration. If the buyer requests a color variation that requires a different powder coating formulation, or a lid variation that uses a different gasket compound, the customized configuration may require new testing and new certification. This is not a changeover cost in the traditional sense-it is a one-time validation cost-but it has the same economic effect of increasing the total cost per SKU for low-volume variations. A buyer who requests ten custom colors may be requesting ten separate certification events, each costing several thousand dollars, if those colors require powder coating formulations that differ from the factory's standard certified palette. The factory may absorb this cost for a high-volume customer with a long-term relationship, but for a one-time order or a new customer, the certification cost per SKU can make small-batch custom variations economically unviable.

The pathway forward requires a fundamental shift in how both buyers and factories approach the customization conversation. Buyers must recognize that variety within a single purchase order is not a neutral specification attribute-it is a cost driver that compounds with each additional variation and that creates scheduling complexity that extends beyond the direct changeover time. Factories must make the variety cost structure explicit and negotiable during the quotation phase, rather than absorbing it as an invisible margin erosion. And both parties must develop a shared vocabulary for discussing the trade-offs between variety, batch size, unit cost, and delivery timeline, so that the buyer's variety request is informed by an understanding of the production realities that the factory must navigate to fulfill that request.

In the end, the misjudgment around order variety in drinkware customization stems from a mismatch between the buyer's transactional perspective and the factory's operational perspective. The buyer sees a single order with multiple options. The factory sees multiple production runs with compounding setup costs. Closing this gap requires making the changeover cost visible, quantifying the variety penalty in commercially intelligible terms, and structuring the quotation process to allow the buyer to make informed trade-offs between customization complexity and total cost. Without this transparency, the variety penalty remains hidden until production begins, at which point the options for managing it have narrowed to schedule extensions, margin sacrifices, or delivery failures-all of which damage the buyer-supplier relationship and undermine the economic viability of custom drinkware procurement.